An Interview with Robin Hobb: Character Writing

I recently had the opportunity to interview prominent fantasy writer Robin Hobb on a variety of subjects. This segment focuses on her character creation and writing process.

Robin Hobb is known for her Realm of the Elderlings universe, spanning five series and more than fifteen books, selling over 1 million copies. George R. R. Martin of Game of Thrones fame describes Hobb’s work as “fantasy as it ought to be written”. One of the things that stands out in her work is the development of her characters.

There are a lot of fantasy books. They almost always stick to a short list of premises and plots and can end up very similar. Hobb’s manages to avoid the Tolkienesque nature which is so prevalent in the fantasy genre. As a result, her work stands out as much as her characters, which for the fantasy reader is like a fresh breath of air.

Many fantasy writers maintain a simplistic view of bad and good. That view can become expected and tiring for readers, for example, when they are delivered yet another mustache twirling villain. But Hobb’s work contains a level of sophistication and complexity that transcends this simple trap of good and evil. For example, the protagonists in her stories, or heroes, typically remain fundamentally flawed. This feels far more relatable and realistic.

How does Hobb create characters?

Forming believable characters is difficult. “Creating a character who is a viewpoint character means that the writer must put that character on like donning a coat. For the time the writer is writing from that character’s point of view, the writer must think and believe as the character does and allow that character to react as he or she truly would,” said Hobb.

According to Hobb, creating more complex characters isn’t about spending hours perfecting details. Instead it requires a different process.

“I think a great deal of writing takes place in a part of my brain that I don’t have conscious access to. So, none of my characters are mapped out by me. It’s more like a character stepping onto a stage in the spotlight, introducing herself, and taking a place in the story,” said Hobb.

Sometimes a character that is created with a specific purpose in mind unfolds and develops into something completely different. Simple plot writers will often put the purpose before the character, as if the characters only existed to serve the greater intent of the story. Conversely, Hobb’s process, living within and wearing her characters, allows her to put the character before the purpose.

One standout example of this is in Hobb’s character The Fool. “I did create an outline for the Farseer Trilogy, but in it, the Fool was a very minor character. He was to encounter Fitz in the garden, exchange some important information, and then step off stage, to be only glimpsed at intervals after that,” said Hobb. “Needless to say, that isn’t how the story worked out. I find that some characters just have their own ideas about the story, and that if I let them have their way, the story becomes much more interesting, and challenging, to write.”

Writing Traumatic Experiences

Another tired cliché found in fantasy, as well as in other types of media, is plot armor. Plot armor renders the hero invincible, for no other reason than their stance as hero.

“In terms of physical trauma, I’m often annoyed by movies in which the protagonist is kicked in the head, slammed against a wall, kicked in the belly, and then rises up and fights on. Often, no one is bruised afterwards, there is no blood, no one limps or throws up in the corner,” said Hobb.

Plot armor sticks out like a sore thumb. It detracts from high stakes conflict by making it meaningless, as the reader already knows who is going to win and lose. There is no sense of danger or possibility of failure.

“That’s just not real. No matter how brave you are, if you get kicked in the head, you brain sloshes around in your skull, and you are likely to have a concussion. Having a good character does not protect you from physical damage. (And, in my personal opinion, scenes like that lead to people thinking they can hit someone with a bat, and not face a possible manslaughter charge!),” said Hobb.

Hobb’s writing is closer the slice-of-life style than to action. But when she does write fight scenes, she writes them effectively. Her physical conflicts serve the characters instead of the plot. This allows her characters to respond in a more nuanced manner. Fans of Hobb’s work also praise her method of writing emotional trauma, as she makes characters a product of their environments.

“The things that happen to us change us. Years later, you will recall the boyfriend who cheated on you and wonder if you should trust your present beau. A child who is abandoned by her parents will have a more difficult time being a good parent herself. I think that is actually what makes a character interesting,” said Hobb.

Hobb writes trauma as an integral part of her characters instead of something sprinkled on for flavor. Every action her characters take is based on deeper reasoning and motivation, resulting in both heroes and villains that are meaningful.

“What shaped that character? Why is she so suspicious of someone being kind to her, why does he think it’s okay to be abusive to someone? We are all the sum of our experiences, good and bad,” said Hobb. “If your character is not shaped by their experiences, what is the point of writing about those experiences?”

Hobb’s Writing as a Whole

Hobb’s writing is not for readers that love action, nor for those seeking feel-good resolutions. Instead, her novels serve as a character study within the realm of fantasy.

“Characters are shaped by their experiences. We become the product of what has been done to us. Or for us,” said Hobb.

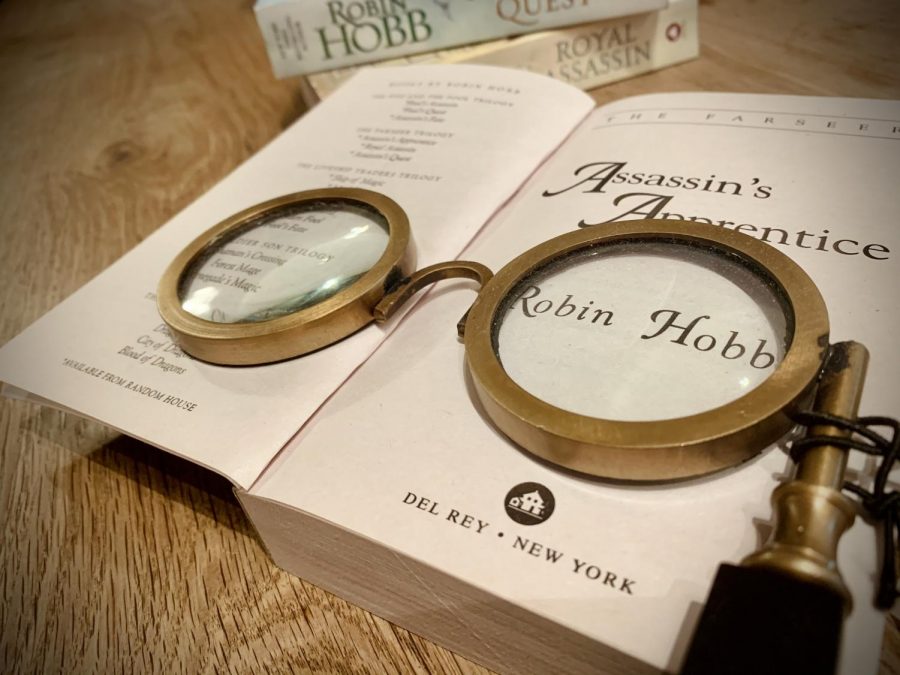

The first book in the Realm of the Elderlings universe is Assassin’s Apprentice. I strongly recommend this series to any fan of the fantasy genre, or for those who enjoy character-based writing. Click here to purchase the book on Amazon.

Madalen Erez is a senior. This is her fourth year on staff. In her free time, she enjoys reading fantasy novels and taking photos of nature.